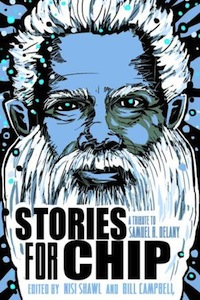

It’s only fitting that Stories for Chip, an anthology honoring professional polymath Samuel R. Delany would feature a ridiculous variety of stories. It’s also only fitting that they would be inventive, incisive, and filled with joy. Edited by Nisi Shawl and Bill Campbell, Stories for Chip includes fiction from every corner of fiction both “literary” and “genre,” as well academic essays on Delany’s place in SFF, and a few personal reminiscences from friends.

That variety in and of itself tells you something vital about Delany: over his career he has written science fiction, fantasy, literary fiction, porn, historical essays, writing advice, and comics, and he’s inspired people in every one of those realms. In a basic way, his very presence in the community inspires because how many black gay intellectuals who also run respected undergrad creative writing programs are there in SFF?

In an interview about with SF Signal, John H. Stevens asked, “What is it about Delany’s writing that is important to you, that you feel needs to be celebrated?” and Shawl’s reply spoke to the many facets of Delany’s life and career:

Well, the writing itself is gorgeous, honest, complex, and elegant–it’s one of humanity’s crowning achievements. So yes, let’s celebrate that achievement. Also, let’s celebrate the fact that this beauty was created by a highly marginalized person, in spite of heavy odds against its creation. Delany is a black man, and thus a racial minority; he’s a gay man, and thus a sexual minority; he’s dyslexic, and thus disabled. Yet instead of winding up murdered or in prison or addicted or insane he has made this incredibly moving art for us to experience.

In his introduction, Kim Stanley Robinson remembers the first time he read a Delany novel (City of a Thousand Suns) and talks about the true wonder in the man’s work: “Delany’s writing is beautiful, which is rare enough; but rarer still, it is encouraging, by which I mean, it gives courage.” He goes on to say that while “Delanyesque” is a perfectly worthy adjective, “Delanyspace” is more apt, as he’s “effected a radical reorientation of every genre he has written in.”

Eileen Gunn’s “Michael Swanwick and Samuel R. Delany at the Joyce Kilmer Service Area, March 2005” tells of an alternate universe, far superior to our own, where Delany’s influence might change the course of Russia. About a hundred pages later, Swanwick himself weighs in to talk about reading The Einstein Intersection as a 17-year-old aspiring writer, and how realizing that all of Delany’s writing choices were also moral choices changed his perception of what writing itself could be. “This is not an easy world to live in, and its inhabitants need all the help they can get.”

Junot Diaz contributes one of his exquisite Yunior stories, “Nilda,” about a troubled girl and the Delany-and-X-Men-loving boy who worships her from afar. Like much Diaz’ fiction, this story would be at home in any literary journal, but his characters’ voices are informed by their love of popular culture, SFF, and their own uncompromising nerdiness. Nick Harkaway’s “Billy Tumult” takes on a psychic noir cum Western that zigzags along to a hilarious conclusion, while Anil Menon’s haunting “Clarity” delves into memory and the perception of reality to give us a haunting story of the unknowability of the human heart. Ellen Kushner’s “When Two Swordsmen Meet” plays with fantasy tropes and expectations to create a fun “what-if?” story. Chesya Burke’s “For Sale: Fantasy Coffin” tells a gripping story of a Nantew yiye, a young girl who can bring the dying back to life, and free haunted souls into the afterlife. But with only three souls left to her, she faces an impossible decision. Thomas M. Disch’s “The Master of the Milford Altarpiece” deconstructs a series of interpersonal relationships while exploring the meaning of envy and love itself, through a series of experimental vignettes that feature a cameo appearance by Delany himself.

The stories that fall more on the SF than F side of things all honor Delany’s tendency to interrogate technology rather than accepting it at face value. Geoff Ryman’s “Capitalism in the 22nd Century” gives us a future world where the internet offers total immersion and instantaneous communication. But even with this, two sisters, raised together, may never understand each other. And in Fabio Fernandes’ “Eleven Stations,” cryosleep technology may give a poet new life, but it doesn’t make it any easier to say goodbye to the old one. And…why has he suddenly begun to levitate?

Kai Ashante Wilson gives us “Legendaire,” which was previously published in Bloodchildren, an anthology of the work of Octavia E. Butler Scholars, echoes Wilson’s upcoming Sorcerer of the Wildeeps in exploring the particular hardships of gods who live among men. A young boy, mortal son of a demigod, seems to have many paths before him: will he be a warrior? A dancer? A kept man? But it could be that all of these paths are illusions, and that his fate was decided while he was still an infant… As always, Wilson’s prose is breathtaking, and this story reads not as fiction, but as an invitation to dance.

My personal favorite story is actually the one co-written by the anthology’s editor. Nisi Shawl and Nalo Hopkinson collaborate on the slightly steampunk “Jamaica Ginger,” a story that begins as a claustrophobic tale of a young girl choosing between two equally grim futures, and, in true Delany fashion, veers off into a completely unexpected direction. It also includes a wonderful mediation on the importance of pockets that will resonate with readers of The Motion of Light in Water.

The literary criticism is as strong and varied as the fiction, highlighting Delany’s vital role as a thinker who is willing to investigate SFF as rigorously as “literary” fiction, and as an SFF historian who works to correct the idea of the genre as a snow white boys’ club.

Walidah Imarisha, the co-editor of the anthology Octavia’s Brood, talks about the time Samuel Delany introduced her to Octavia Butler, and spins off of that meeting to talk about how his life and writing has been an exercise in intersectionality that literally rewrote the reality of SFF for many readers:

So long seen as the lone Black voice in commercial science fiction, Delany held that space for all the fantastical dreamers of color who came after him. The space he held was one in which we claimed the right to dream. To envision ourselves as people of color into futures, and more, as catalysts of change to create and shape those futures….Delany was instrumental in supporting the decolonization of my imagination, truly the most dangerous and subversive decolonization process, for once it has started, there are no limits on what can be envisioned.

Isiah Lavender’s “Delany Encounters: Or, Another Reason Why I Study Race and Racism in Science Fiction” looks at the ways Delany frames race in his writing, and then turns to his foundational role in the concept of Afrofuturism, and his use of hope:

Hope fuels the fundamental emotional drive that foments resistance, rebellion, and subversive writing by and for black people. Hope unsettles the white order of things. Hope also makes allies between the races.

Finally L. Timmel Duchamp’s “Real Mothers, a Faggot Uncle, and the Name of the Father: Samuel R. Delany’s Feminist Revisions of the Story of SF” is a fascinating and stirring look at how SF’s obsession with legitimacy has lead to the erasure of feminist voices in SF, and then particularly delves into some of Delany’s work building from Jeanne Gomoll’s “An Open Letter to Joanna Russ” to correct SF’s genealogy. Delany, Timmel argues, is not asking for historians to insert a few female or Black authors into the usual history, rather, he’s calling for nothing less than a revolutionary reworking of the story we tell about science fiction, and a further dissolution of boundaries between “genre” and “mainstream.”

Samuel Delany’s life and career has demolished any limitations society tried to lay on him, and, luckily for all of us, many brilliant writers found things a little easier in his wake. Many of them are represented in this anthology, and my advice to all of you is to read Stories for Chip, and then read some of Chip’s own stories!

Stories for Chip is available now from Rosarium Publishing.

Leah Schnelbach wants to live in Babel-17. Come, infect her with your language virus on Twitter!

Thank you so much for your insights. Very moving to me. Last night we launched the anthology with a University Book Store reading by five contributors, and this morning I’m still feeling sort of dreamy about the impact of Stories for Chip on our wonderfully astute audience.

Must Get…….

Can’t wait to read this. Will jump to the top of my queue once my Indiegogo ebook arrives. Wish I could have made it to the reading last night.

No kindle cersion or epub means no me, unfortunately. :(

And no, I dont hate books, I am extremely visually impaired, so there is quite a few times I miss out on something that looks to be very special.

Woah, I see now there IS both mobi and epub, they just dont appear as buyable on the publishers site? REALLY want to read this, and with my eyes, that would be the only way!

For anthologies, Rosarium are great. Great writers and great ideas. For novels and comics, I don’t buy them, since many writers have said they doesn’t pay up royalties owed.